Turns Out Composing Music for VR Is Not Exactly Simple

Turns Out Composing Music for VR Is Not Exactly Simple

One of the many games available on the Oculus Rift is Farlands, an exploration title that plays out like a laid back safari through a peaceful alien planet. The otherworldly zoo is supported by veteran composer Jason Graves’ pleasant, ethereal score. Graves has previously composed music for industry hits like the Dead Space series, Tomb Raider, and Far Cry Primal, but took a break from the intense world of action gaming to craft a score for virtual reality.

We got the opportunity to talk to Graves about games, his process, and what it’s like to compose music that’s truly interactive.

What was it like to compose for VR as opposed to a more familiar console experience?

From a technical standpoint, there’s a lot to consider when making a VR game, because there’s not just a 3D visual world — you’ve also got a 3D audio world. Just because you can do a lot of things, though, doesn’t mean you should.

Restraint is a good word to use. With the music more than the sound effects, a lot of times, less is more.

In addition to the score, do you get drafted to do cues, as well?

Depends on the game; I actually love doing stuff like that because you get this real sense of immersion from the score. It makes everything sound like it comes from the same world.

I tend to give developers lots of options and layers, so they have more control over the final product. So, we did a lot of “Victory” and “End of the Day” and those kind of sound cues for Farlands that were made up of sounds that I used in the score itself.

Do you think about your music appearing out of order when you’re composing it?

When I’m dealing with short pieces, I do try to write them so that they can be interchanged and randomized. The biggest pleasure I get is doing some things and sending them to the developer and then hearing them in the game and being surprised.

That’s what’s supposed to happen. It’s interactive. The player is determining the score. There’s a symbiosis between the gameplay and the music in ways that I could never accomplish if I just sat down and wrote a static piece of music.

How much creative freedom did you get going into the Farlands project?

Enough to hang myself with.

But, that’s honestly the way it’s been for the last six years or so. I’m given a lot of creative freedom within projects, but the understanding is that I’m being creative within the sandbox established by the game. Farlands was no exception. There was a surface-level discussion with the creative director and a few others when I visited Oculus, and no one talked about specific instruments or genres.

What everyone talked about were the feelings they wanted to evoke, which is really what music comes down to anyway. Then, they left it to me to figure out how that would sound.

When you worked on Evolve, producers mandated a non-orchestral score, and when you worked on Far Cry Primal, you collected a variations on wood and brick to create the score. Where does that motivation come from?

A lot of it really came from game developers saying, “Hey, what can you do that would be different? We want something iconic and unique where we can hear five seconds of the music and know it’s our score.” I mean, that’s easier said than done, but when you start using original sounds, and you’re not confining yourself to “traditional” instruments, then you’ve got more opportunities to create something memorable.

When I realized that game developers were going to let me have fun and do some really experimental things that even I wasn’t sure would work, it just created this snowball effect that’s grown from project to project.

Do you think your rhythmic bent has helped distinguish you from the competition?

I really hope so. In school, I felt like I was at a disadvantage. I was worried that I didn’t know how to fill in the blanks, I wished I’d studied piano more than drums. Then, after I scored the first Dead Space game, I discovered that I was very comfortable with rhythm. And, for me, that’s the heart and soul of music. From there you build up pitch and harmonies, but the rhythm is the base.

Once I embraced being a drummer and really leaning on as a strength has really shaped the music I write. Of course, on my own, I’m still learning about orchestration and composition, but that’s what makes this job so much fun. Every day, I get to come into the studio and learn something new.

What would you say you learned while composing Farlands?

Farlands was so relaxing and meditative. I learned how to use space, both in terms of physical distance and space in the sound itself. I didn’t want to have music playing all the time, even when the song was going. Hopefully, there’s an ebb and flow to the final product.

Of all the game’s you’ve worked on, which score is your favorite?

Well, that’s tough, because all of the scores I’ve worked on were kind of ripped from my hands and completed without me. I wouldn’t have that any other way, because otherwise I’d never finish anything, but if I had to pick some, there were three games that kind of tie for first. The first was Dead Space 2, because we weren’t even sure we’d get the opportunity to do it in the first place.

The second would probably be The Order: 1886. Sony literally let me do anything, so I had this crazy orchestra with no violins and no brass, no high woodwinds. It was just all male singers, low strings and low woodwinds, which gave it a slightly somber score.

I also have really good memories of Far Cry Primal because it was all live, but it was all done entirely by me in my small studio at home. I learned so much about how to layer music and make new, big sounds.

This interview was edited for brevity and clarity.

In order for a VR music application to control and manipulate external devices, the software must be able to communicate by way of the MIDI protocol - and that's an exciting development in the field of music creation in VR!

In order for a VR music application to control and manipulate external devices, the software must be able to communicate by way of the MIDI protocol - and that's an exciting development in the field of music creation in VR!

Since 2001, the famous

Since 2001, the famous  Enter

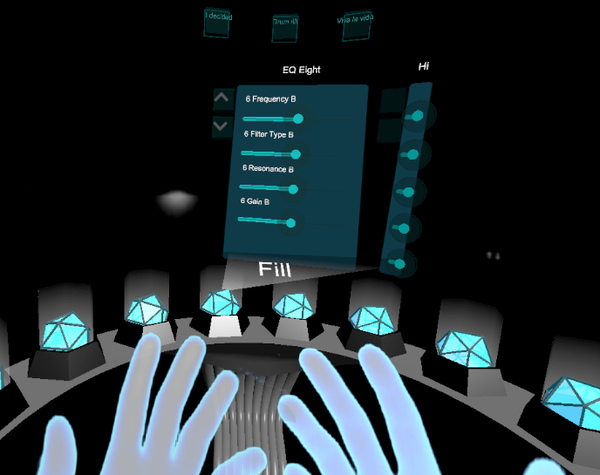

Enter  The composer controls the sounds in the VR space with hand motions, as pictured to the right. Special gloves worn by the performer deliver motion tracking data to a set of two sensors that relay this data to the Pensato application. While this is going on, Pensato is also projecting the images from the VR headset to a set of three projectors for the audience to enjoy. The result is a futuristic presentation that lends a new level of sci-fi slickness to the performances of any electronic artist or DJ.

The composer controls the sounds in the VR space with hand motions, as pictured to the right. Special gloves worn by the performer deliver motion tracking data to a set of two sensors that relay this data to the Pensato application. While this is going on, Pensato is also projecting the images from the VR headset to a set of three projectors for the audience to enjoy. The result is a futuristic presentation that lends a new level of sci-fi slickness to the performances of any electronic artist or DJ. Last month, the National Association of Music Merchants staged its annual Summer NAMM 2016 convention in the Nashville Music City Center. Over 1,500 product brands in the professional music equipment industry showcased their hottest products to a convention crowd of musicians, music retailers and audio industry experts. The show floor teemed with the usual plethora of booths devoted to microphones, DSP racks, guitars, keyboards, DAWS, and other pro audio gear.

Last month, the National Association of Music Merchants staged its annual Summer NAMM 2016 convention in the Nashville Music City Center. Over 1,500 product brands in the professional music equipment industry showcased their hottest products to a convention crowd of musicians, music retailers and audio industry experts. The show floor teemed with the usual plethora of booths devoted to microphones, DSP racks, guitars, keyboards, DAWS, and other pro audio gear. According to the product description, The Music Room "will make you a multi-instrumentalist" by providing an assortment of virtual reality instruments hosted inside their VR environment. The software comes bundled with a selection of virtual instruments, which the developers at

According to the product description, The Music Room "will make you a multi-instrumentalist" by providing an assortment of virtual reality instruments hosted inside their VR environment. The software comes bundled with a selection of virtual instruments, which the developers at  In addition to these bundled instruments, The Music Room also comes with a simple, compact Digital Audio Workstation application called

In addition to these bundled instruments, The Music Room also comes with a simple, compact Digital Audio Workstation application called

The AeroMIDI software predates the emergence of consumer VR. It was first introduced by

The AeroMIDI software predates the emergence of consumer VR. It was first introduced by  The makers of the software, Acoustica Inc, describe AeroMIDI as "the virtual 3D glue between your music and your hands." As seen in the picture to the right, the visual interface consists of an array of three dimensional blocks and cubes that can represent both note values and expression changes (such as vibrato, pitch bend, low pass filter, volume, or whatever other parameters the user wishes to manipulate).

The makers of the software, Acoustica Inc, describe AeroMIDI as "the virtual 3D glue between your music and your hands." As seen in the picture to the right, the visual interface consists of an array of three dimensional blocks and cubes that can represent both note values and expression changes (such as vibrato, pitch bend, low pass filter, volume, or whatever other parameters the user wishes to manipulate).